- Home

- Vladimir Nabokov

Letters to Véra

Letters to Véra Read online

Vladimir Nabokov

LETTERS TO VÉRA

Translated and edited by Olga Voronina and Brian Boyd

Contents

List of Plates

List of Abbreviations

Envelopes for the Letters to Véra

Brian Boyd

‘My beloved and precious darling’: Translating Letters to Véra

Olga Voronina

LETTERS TO VÉRA

Plates

Appendix One: Riddles

with Gennady Barabtarlo

Appendix Two: Afterlife

Brian Boyd

Notes

Chronology

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Follow Penguin

List of Plates

All illustrations from the Estate of Vladimir Nabokov, unless otherwise noted.

Nabokov family at Vyra, their summer estate, 1907

The five Nabokov children, Yalta, 1919

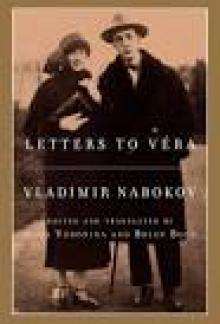

VN and VéN, Berlin, c. 1924

VN and pupil Aleksandr Sack, Constance, 1925

VN, Berlin1926

VéN, Berlin, 1927

Yuly Aykhenvald

Ilya Fondaminsky

Savely and Irina Kyandzhuntsev, Nicolas and Nathalie Nabokov and VN, Paris, 1932

Ivan Bunin (Foto Centropress Prague, Leeds Russian Archive)

Vladislav Khodasevich (Nina Berberova collection)

VN, VéN and DN, Berlin, 1935

Elena Nabokov, Prague, 1931

Irina Guadanini (Private collection)

VN with editorial board of Mesures, near Paris, 1937 (Gisèle Freund)

VN, VéN and DN, Cannes, 1937

VN and VéN, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1942

VN and VéN, Ithaca, New York, 1954

VN and VéN, dictation, Montreux, c. 1968 (Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

VN and VéN, lepping (butterfly hunting), near Montreux, c. 1971 (Horst Tappe)

VN and VéN, Montreux, 1968 (Philippe Halsman)

List of Abbreviations

Books are by Vladimir Nabokov unless otherwise noted. For full bibliographical details, see Bibliography. This list includes abbreviations used in the letterheads.

AL autograph letter, unsigned

ALS autograph letter, signed

AN autograph note

ANS autograph note, signed

APC autograph postcard, unsigned

APCS autograph postcard, signed

BB Brian Boyd

DBDV Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: The Nabokov–Wilson Letters, 1940–1971

DN Dmitri Nabokov

EN Elena Nabokov (mother)

EO Alexander Pushkin, Eugene Onegin, trans. with commentary by Vladimir Nabokov

Gift The Gift

KQK King, Queen, Knave

LL Lectures on Literature

LRL Lectures on Russian Literature

MCZ Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University

MUSSR The Man from the USSR and Other Plays

NG Nikolay Gogol

N’sBs Nabokov’s Butterflies

PP Poems and Problems

RB Russian Beauty and Other Stories

Schiff Stacy Schiff, Véra (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov)

SL Selected Letters 1940–1971

SM Speak, Memory

SO Strong Opinions

Sog Soglyadatay, 1938

SoVN Stories of Vladimir Nabokov

SP Selected Poems

Stikhi Stikhi, 1979

TD Tyrants Destroyed

TGM Tragediya gospodina Morna

TMM The Tragedy of Mister Morn

V&V Verses and Versions

VC Vozvrashchenie Chorba

VDN Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (father)

VéN Véra Nabokov

VÉNAF Véra Nabokov audiofile (for 1932 letters, from BB tape recording)

VF Vesna v Fial’te

VN Vladimir Nabokov

VNA Vladimir Nabokov Archive, Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, New York Public Library

VNAY Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years

VNRY Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years

Envelopes for the Letters to Véra

Brian Boyd

I dreamt of you last night–as if

I was playing the piano and you

were turning the pages for me.

VN to VéN, 12 January 1924

I

No marriage of a major twentieth-century writer lasted longer than Vladimir Nabokov’s, and few images anywhere encapsulate lasting married love better than the 1968 Philippe Halsman photograph of Véra nestled under her husband’s right arm and looking up towards his eyes with steady devotion.

Nabokov first wrote a poem for Véra in 1923, after having spent only hours in her company*, and in 1976, after over half a century of marriage, dedicated ‘To Véra’ the last of his books published in his lifetime. He first dedicated a book to her in 1951–his autobiography–whose last chapter turns directly to an unidentified ‘you’: ‘The years are passing, my dear, and presently nobody will know what you and I know.’ He had anticipated the sentiment in a letter to Véra, barely a year into their relationship: ‘you and I are so special; the miracles we know, no one knows, and no one loves the way we love’.

Nabokov would later call his marriage ‘cloudless’. He had done so even in a letter to Irina Guadanini, with whom he fell into an intense affair in 1937. That year was the darkest and most painful in the Nabokovs’ marriage, and an exception, as the letters attest. But although the sun of young love shines or shimmers in many of the early letters, other troubles becloud much of the correspondence: Véra’s health and his mother’s, their constant shortage of money, their distaste for Germany, and his exhausting search for refuge for his family in France, England or America as Hitler’s rise threatened the very existence of the Russian émigré community where he had shot to not-quite-starving stardom.

Véra Slonim first encountered Vladimir Nabokov as ‘Vladimir Sirin’, the pen-name he had adopted in January 1921 to distinguish his own byline from that of his father, also Vladimir Nabokov. Nabokov senior was an editor and founder of Rul’, the Russian-language daily in Berlin, the city that in 1920 had become the centre and magnet for the post-1917 Russian emigration. Nabokov junior had been publishing books and contributing to journals in Petrograd since 1916, when he still had two years of high school to complete, and by 1920, in the second year of his family’s emigration, his verse was already being admired by older writers like Teffi and Sasha Chorny.

Much of the time Letters to Véra features unfamiliar profiles of Vladimir and Véra. The familiar images begin when Nabokov added the first dedication ‘To Véra’ in 1950, exactly halfway through the story of their love. And when Lolita was published in America in 1958, and in the years that followed, a flood of translations of his old Russian oeuvre, as well as his new English work–fiction, verse, screenplay, scholarship and interviews–would appear with more dedications to Véra. The writer and his wife were photographed together in the many interviews his fame precipitated, and the story of her editing, typing, driving, teaching, corresponding and negotiating for him became part of the Nabokov legend. Yet the second half of their life together, from 1950 to 1977, occupies only 5 per cent of the letters that follow, and the remaining 95 per cent reflects years much more strained than this final spell of worldwide fame.

The Slonim family (father Evsey, mother Slava, and daughters Elena, Véra and Sofia) escaped Petrograd via many adventures in Eastern Europe before settling in Berlin early in 1921. There, Véra told me, she was ‘very well aware’ of Nabokov’s talent before she met him, ‘despite having lived in non-literary circles, especially among former officers�

�. (A strange choice of company, perhaps, for a young Russian-Jewish woman, given the anti-Semitism common in the White army. But Véra’s own courage as she and her sisters were fleeing Russia had turned a hostile White soldier from aggressor to protector, and she insisted to me there were many decent former White officers in Berlin.) The earliest samples of his verse she had clipped from newspapers and journals date from November and December 1921, when she was still nineteen and he twenty-two. A year later the young Sirin, already richly represented in émigré periodicals and miscellanies, as a poet, short-story writer, essayist, reviewer and translator, scooped the productivity stakes in Berlin’s émigré book world: Nikolka Persik, a translation of Romain Rolland’s 1919 novel Colas Breugnon, in November 1922; a sixty-page collection of recent verse, Grozd’ (The Cluster), in December 1922; a 180-page collection of verse over several years, Gorniy put’ (The Empyrean Path), in January 1923; and a translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Anya v strane chudes (Anya in the Land of Wonders, March 1923).

Of much more interest for one attractive and strong-willed young woman with a passion for literature was the evidence of a romantic rift in Sirin’s recent verse. In the wake of the assassination of his father on 28 March 1922, Nabokov had been allowed by the parents of the vivacious beauty Svetlana Siewert to become engaged to her, despite her being much younger than him, seventeen to his twenty-three. Poems he wrote for Svetlana within the first year of his knowing her filled the volume of his most recent verse, Grozd’. But on 9 January 1923, he was told that the engagement was over: she was too young and he, as a poet, much too uncertain a prospect.

If meeting Svetlana had released a torrent of verse, so did parting from her. Over the next few months, a number of poems reflecting the poet’s loss in love began to appear in the émigré press: ‘Zhemchug’ (‘The Pearl’) in March (‘like a pearl-diver sent to know the depths of passionate torments, I have reached the bottom–and before I can bring the pearl back to the surface, I hear your boat above, sailing away from me’); ‘V kakom rayu’ (‘In what heaven’), also in March (‘you have captured my soul in era after era, and have just done so once again, but once again you have flashed on by, and I am left only with the age-long torment of your elusive beauty’); the most explicit, ‘Berezhno nyos’ (‘I carefully carried’), on 6 May (‘I carefully carried this heart for you but someone’s elbow knocked it down and now it lies shattered’).

Another poem, ‘Ya Indiey nevidimoy vladeyu’ (‘The Ruler’: ‘An India invisible I rule’), written the same day as ‘I carefully carried’, and published on 8 April, signals a readiness for a new beginning: the poet is an emperor of the imagination, and swears he can conjure up untold wonders for a new princess–though she, whoever she will prove to be, remains still unseen. The princess, though, may well have seen the poem, as well as the glimpse of the end of romance in the other poem that Nabokov wrote the same day. For on 8 May 1923, two days after the poem ‘I carefully carried’ appeared in Rul’, Véra Slonim appeared before Vladimir Sirin, wearing, and refusing to lower, a black Harlequin demi-mask. Nabokov would later recall meeting Véra at an émigré charity ball. Rul’, the exhaustive record of émigré Berlin, notes only one charity ball around that date, on 9 May1923, although it is 8 May that the Nabokovs would continue to celebrate as the day of their first meeting. When I cited to Véra her husband’s account of their meeting, and the evidence in his diaries for 8 May as the day they commemorated, and the evidence from Rul’ of a 9 May charity ball, she responded: ‘Do you think we do not know the date we met?’

But Véra was an expert at blanket denial. Whatever we do not know of ‘what you and I know’, at an émigré charity ball Véra singled out Vladimir Sirin, while keeping a mask up to her face. Nabokov’s favourite sibling, Elena Sikorski, thought Véra wore that mask so that her striking but not unmatchable looks would not distract him from her unique assets: her uncanny responsiveness to Sirin’s verse (she could commit poems to memory on a couple of readings) and her sensibility uncannily in tune with the one behind the poems. They stepped outside together into the night, they walked the Berlin streets, marvelling together at the play of light and leaf and dark. A day or two later, Nabokov set off for a planned summer as a farm labourer on an estate in the south of France managed by one of his father’s colleagues in the Crimean Provisional Government of 1918–19, in the hope that the change would help dull his grief at his father’s death and his severance from Svetlana.

On 25 May, from the farm of Domaine-Beaulieu, near Solliès-Pont, not far from Toulon, Nabokov wrote Svetlana one last forbidden farewell letter, full of passionate regret, ‘as if licensed by the distance that separated them’. A week later he wrote a poem to the new possibility in his life:

THE ENCOUNTER

enchained by this strange proximity

Longing, and mystery, and delight ...

as if from the swaying blackness

of some slow-motion masquerade

onto the dim bridge you came.

And night flowed, and silent there floated

into its satin streams

that black mask’s wolf-like profile

and those tender lips of yours.

And under the chestnuts, along the canal

you passed, luring me askance.

What did my heart discern in you,

how did you move me so?

In your momentary tenderness,

or in the changing contour of your shoulders,

did I experience a dim sketch

of other–irrevocable–encounters?

Perhaps romantic pity

led you to understand

what had set trembling that arrow

now piercing through my verse?

I know nothing. Strangely

the verse vibrates, and in it, an arrow ...

Perhaps you, still nameless, were

the genuine, the awaited one?

But sorrow not yet quite cried out

perturbed our starry hour.

Into the night returned the double fissure

of your eyes, eyes not yet illumed.

For long? For ever? Far off

I wander, and strain to hear

the movement of the stars above our encounter

and what if you are to be my fate …

Longing, and mystery, and delight,

and like a distant supplication ...

My heart must travel on.

But if you are to be my fate ...

The young poet knew that the young woman who had accosted him so strangely followed his verse assiduously. He sent this new poem to Rul’, where it featured on 24 June. Here, in a sense, Vladimir’s letters to Véra begin, in a private appeal, inside a public text, to the one reader who could know about the past the poem recorded and the future it invited.

Just as Nabokov had responded in verse to Véra’s bold response to the heartache of Sirin’s recent verse, so Véra appears to have responded boldly to this new verse invitation. She wrote to him in the south of France at least three times during the summer. The letters do not survive–the highly private Véra later destroyed every letter of hers to Vladimir that she could find–so that we cannot be sure that her first letter followed the appearance of ‘The Encounter’ in Rul’, but the logic of their passion strongly implies such a sequence. She had made her masked appeal to him in person on 8 May, and could not know whether she had roused more than a passing interest. Reading Rul’ on 24 June, she could know that he wanted her to know the effect she had had and the hopes she had stirred.

If Véra wrote to Vladimir almost immediately after reading the poem, Vladimir may have responded to her first letter with another poem, ‘Znoy’ (‘Swelter’), that he wrote on 7 July. Here he hinted at his desire stirring in the heat of a southern summer. He did not send it to her yet, but after at least two more letters from her, he wrote another poem, on 26 July (‘Zovyosh’–a v derevtse granatovom sovyonok’: ‘You call–and in a little pom

egranate tree an owlet’). He then wrote his first letter to her, just a few days before his planned departure from the farm, enclosing both ‘poems for you’. He begins this first letter with memorable abruptness and no salutation (‘ I won’t hide it: I’m so unused to being–well, understood, perhaps,–so unused to it, that in the very first minutes of our meeting I thought: this is a joke, a masquerade trick ... But then ... And there are things that are hard to talk about–you’ll rub off their marvellous pollen at the touch of a word ... They write me from home about mysterious flowers. You are lovely ... And all your letters, too, are lovely, like the white nights’), continues with the same sureness (‘Yes, I need you, my fairy-tale. Because you are the only person I can talk with about the shade of a cloud, about the song of a thought’) and ends, before offering her the poems, with ‘So I will be in Berlin on the 10th or 11th ... And if you’re not there I will come to you, and find you’.

From here, Vladimir’s first letter to Véra, we need to follow the trail chronologically, to orient the letters in their life, their love and their world, before considering what makes the correspondence so special and what light it throws on Nabokov as man and writer.

At the end of summer 1923 he found Véra in Berlin with her mask and guard down. Like other young lovers with no space of their own, they would meet day after day to stroll together on the evening streets. A single letter of this time, dated November 1923, from Vladimir in one part of Russian west Berlin to Véra in another, reflects their passionate early understandings and misunderstandings.

At the end of December 1923, Vladimir travelled with his mother and his youngest siblings, Olga, Elena and Kirill, to Prague, where his mother, as the widow of a Russian scholar and statesman, was entitled to a pension. In their first stretch of weeks apart, Vladimir wrote to Véra of his intense focus on his first long work, the five-act verse play Tragediya gospodina Morna (The Tragedy of Mister Morn), of his impressions of Prague (looking out at the frozen Moldau: ‘along that whiteness, little black silhouettes of people cross from one shore to the other, like musical notes ... some boy is dragging behind him a D-sharp: a sledge’), and of the shock of being without her for almost a month.

Lolita

Lolita Laughter in the Dark

Laughter in the Dark Despair

Despair Mary

Mary The Enchanter

The Enchanter Pnin

Pnin Transparent Things

Transparent Things The Real Life of Sebastian Knight

The Real Life of Sebastian Knight Bend Sinister

Bend Sinister Invitation to a Beheading

Invitation to a Beheading The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov

The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov The Eye

The Eye Letters to Véra

Letters to Véra Speak, Memory

Speak, Memory The Gift

The Gift The Luzhin Defense

The Luzhin Defense Pale Fire

Pale Fire Glory

Glory Man From the USSR & Other Plays

Man From the USSR & Other Plays Vladimir Nabokov: Selected Letters 1940-1977

Vladimir Nabokov: Selected Letters 1940-1977 Strong opinions

Strong opinions Look at the Harlequins!

Look at the Harlequins! The Tragedy of Mister Morn

The Tragedy of Mister Morn Ada, or Ardor

Ada, or Ardor Lectures on Russian literature

Lectures on Russian literature King, Queen, Knave

King, Queen, Knave The Original of Laura

The Original of Laura